My Oulu: One year since the war in Ukraine – lost and gained dreams of the Ukrainian Community interlace in Oulu

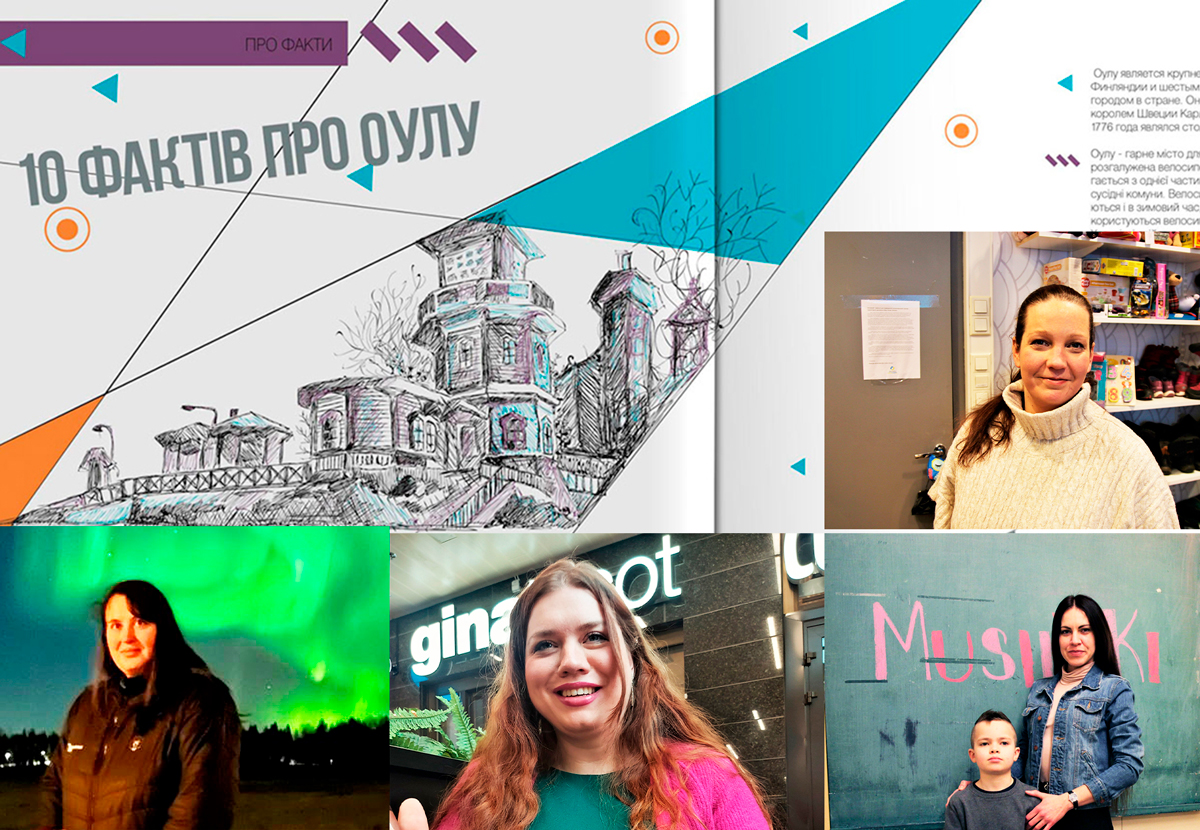

Last year about 45000 of Ukrainians fled to Finland and over and 1500 of them, reside in and around Oulu. Photos: Lölä Vlasenko

The Ukrainian citizens are continuing to leave the country as Russian troops are committing war crimes, attacking civilians and vital infrastructure, turning cities into ruins.

According to the United Nations, thousands and thousands of civilians were killed in Ukraine, including hundreds and hundreds of children. The number of killed and wounded Ukrainian forces varies in different sources, but includes thousands of people. Ukraine is facing a huge energy crisis, surviving the winter without proper electricity, heat and water supplies.

Over 45000 of Ukrainians fled to Finland, according to the Finnish Ministry of Interior which assessed the same amount of refugees coming from Ukraine in 2023. Over 1500 of them, according to the latest Finnish Immigration Service data, reside in and around Oulu.

How are they surviving and how has their relationship with Finland been developing so far? What is there along the pain and what hopes stand alongside the hope for the victory?

Mosaic of dramas

Stories of refugees escaping Ukraine are equally heart-breaking and uniquely breathtaking. One no less captivating than the other, they sound like an award winning scenario for a blockbuster, with elements of a psychological thriller, with emergency packing, quick goodbyes with the loved ones for unpredictable time, leaving all behind; with the lack of food, water and sleep and fear ahead of the unknown.

Anna Halytska is telling about a packed evacuation train she had been fleeing to Poland last March from Odessa, a southern big port city of Ukraine, with her then 4 year old daughter Olivia and husband with special needs.

”We were waiting long hours without water, there was basically no option to move in that train, it was so full. The volunteers in Poland helped us go to Finland by air. It was our first flight ever, so exciting. We have always wanted to come to Finland one day and my mother has been researching and said it is one of the best countries to live in. When we came to the Finnish family which was ready to host us, the first impression was the smell, such a wonderful smell of wood! And outside all around was the snow, back at home we had been having Spring weather. My kid loves the snow”, Anna Halytska says.

She is an engeneer and was working maintaing a windmill area last Summer, now she is trying to find a job. She is one of those Ukrainians who would want to stay in Finland no matter when and how the war ends. According to the Finnish Ministry of Interior survey, this is the plan for one of three Ukrainians.

What is common for all of them is the deep gratitude towards the Finnish people.

Kindness as a therapy

”Finnish people touched us deeply with their big hearts, they are amazing, honest, friendly, kind and caring. So many greeted us saying ”Slava Ukraine!” Praise Ukraine! Tears appeared in my eyes, this means so much more than a greeting”, says Anastasiia Yemelina who came from the Southern city of Mykolaiv with her then 6 year old son Ostap last June.

Mykolaiv was suffering Russian shellings every day, the missiles killed tens of civilians and destroyed the water pipeline leaving the city with no water to drink. Anastasiia says the Russian shelling destroyed the house next to the one her parents live in, the shrapnel flying just a few centimeters near her car. She tells about making a little shelter in a bathroom for her son and then running to the dusty bomb shelter, packed with people in terror – that was the routine their life became after the war had started.

”When I was there I thought every day was the last one and tomorrow wouldn’t come… That is the way it turned out for so many who died in the war! Of course this forever stays in our memory and is impossible to forget”, she says.

Anastasiia Yemelina tried to receive psychological help for her son in Finland, but was told it was too hard to get, in spite of the fact that so many Ukrainian refugees have more or less symptoms of post traumatic stress syndrome.

Now Ostap goes to school and enjoys hobbies, he especially likes drawing. The pictures of tanks slowly made place to Aurora Borealis above the winter forest.

”It was hard to explain to the child that he is in a safe country, that he doesn’t have to be afraid to go outside, that he can sleep in peace all night and doesn’t have to wake up with the missile alarm signal. For me the hardest was to sort out my thoughts, learn to enjoy life and start to be happy, while all my family has stayed in Ukraine”, Anastasiia Yemelina adds.

Anastasiia Yemelina assumes that for the most Ukrainian people one of the hardest questions is whether they will be staying in Finland.

”We don’t know what tomorrow brings – we can’t make long term plans, much depends on how long the war lasts. We love our Ukraine so much! We are comfortable there, but a big but is to think about your child. My goal as a mom is to sustain a comfortable life for him, provide him with a good education and a good basement for implementing his dreams”.

Difficult feedback

Anastasiia Yemelina believes the comfort of Ukrainian refugees would improve if they got a chance to live in separate apartments. Now many share an apartment with other families from Ukraine, which is not always helping to live a peaceful life.

She says that, repeating how grateful her family and Ukrainian friends are for everything they have received in Finland: clothes, food, schools and daycare for children and Finnish and English language courses for the adults.

”Many think that if you say what you think, you might be considered ungrateful, this is something we are unlearning now”, says Iryna Demchuk, a graphic designer from Kyiv and one of the youngest female activists of Ukrainian Help Centre.

”It is a common misconception in the refugees’ community that one shouldn’t have any negative feedback on anything. But if you say your opinion, it doesn’t mean you don’t like Finland – everybody likes Finland! It is beautiful and safe,” she adds.

Few days before the war started she went on a trip to Budapest.

”It was one of those vacations where you don’t take your laptop or anything except for a few beautiful dresses, just to chill. And then, in a few days I find myself in Northern Finland receiving underpants as a charity from strangers and crying – both of grief and of people’s kindness.”

She says she had everything in Ukraine and Ukraine had everything. The country was developing its economy and democracy, systematically fighting the leftovers of corruption which had been poisoning the country as a post-Soviet legacy.

Her sister, a professional piano player and teacher, had been living and studying in Oulu for ten years and invited Ira to Oulu and inspired her to draw. Iryna has so far been the only Ukrainian artist to have had an exposition in Oulu, in the space of Voimala. Back in the days in Kyiv Iryna had been doing a sketch on Oulu for a Ukrainian tourist brochure, saying how lovely the city is for travelling. She still thinks so.

”Mom has always said I should follow my sister and live in Finland. Finland is a wonderful country, I like it. But it is not for me. I would never think I would be living here for a year. I dream of getting back to Ukraine in Spring.”

Her parents live in a small town just seven kilometres from Poland which, although a missile struck Poland near Ukrainian border and killed at least two people in November, serves as a certain protection from Russian shellings, she believes.

”People don’t pay enough attention to politics, which leads to indifference and hatred and aggression. It is common that politics and religion are tabooed like women’s periods,” Iryna Demchuk says.

Just like her fellow Ukrainians she hasn’t expected the war to last the whole year and is hesitating to predict how long it lasts.

”I haven’t lived in Russia and can’t understand how propaganda can force people to kill. It is unavoidable to accept the national responsibility for what is happening, the Germans succeeded in it after all. No choice is a choice. I hate the phrase ”We can’t do anything”. Everyone can do at least something”.

Hidden struggle

Many Russian volunteers under the threat of jail and physical harm have been helping Ukrainians escape Russia – many Ukrainians had to get to Russia through the so-called ”humanitarian corridors” – often being the only way to escape the zone of hostilities and war crimes.

This is how Ukrainians go through two hells, one of the war and the other of having to stay on the aggressor’s territory. The volunteers work as partizans helping Ukrainians flee to Europe, one gets up to fifteen years in jail in Russia for calling the ”war” the ”war”, and Russian jail is a tough place to survive in, full of physical and psychological torture, with no rule of law in general.

Amina Kazanskaya, name changed for security reasons, one of Russian veteran volunteers helping Ukrainians flee, expresses her gratitude to the Finnish people just as Ukrainian refugees do.

”Ukrainian refugees who ended up in Russia had no other choice, there is no reason to consider them pro-Putin. It is amazing that many refugees run to the aggressor country. They are confused, whether they should go to Europe where everything is alien to them, or stay in Russia, where it is scary, but where they have some relatives and familiar language. Some waited that everything would end on its own, this is why many times I came across a situation when people came to Russia in Summer or Spring in 2022, but fled Russia after half a year or later”, Kazanskaya tells.

”The border guards in Estonia, for example, are outraged in these cases being picky about everything. Finnish border guards are much friendlier, many thanks to them for this! Ukrainian refugees of course are scared of asking help to flee Russia – this is hard to overcome, yet possible – there is no other way in the end. I can’t comment about volunteers’ work because each comment is a clue for Russian authorities, and we have to think about our safety. But there are really many of us”, she says.

Superwomen in Oulu

Mona Hyvärinen is one of the leaders of Ukrainian Help Centre. She has found many homes for Ukrainian families now hosted by Finnish people as the refugee center in Heikinharju has been quickly becoming full. She also works with Ukrainian refugees in Oulu University of Applied Sciences (OAMK) in SIMHE-Ukraina team. She believes the relationship between the Ukrainian community and Finland has been developing better than with any other refugees earlier.

”Maybe one of the reasons is not that big cultural difference, maybe it is the fact that people from Ukraine are mainly women and kids, and they are in a weak position. So it is easier for people to come closer to them and communicate”.

Hyvärinen believes it is important to maintain events and places for such communication, one of the options being library activities.

The Help Centre which recently won the status of ”Vuoden oululainen” is turning into an association so that Ukrainian refugees can get more services and help under the same roof. Mona Hyvärinen hopes it will be supported by the Finnish citizens – all the help is provided by volunteers.

“War has come closer to Finland than before, and there is a lot of fear in the air. People are afraid that if it is possible to happen in Ukraine, it is possible to happen in Finland too. Finnish people understand the Ukrainian situation pretty well, so it is mostly understanding in both ways,” Hyvärinen concludes.

The Ukrainian women became a feminist pride having had to take the role of single mothers, while their husbands are at war or cannot leave the country due to mobilization laws. Not only they establish a new life here, look for jobs, study Finnish and English, they also help children to integrate into the new world – and a lot also maintain distant online education for their children in Ukrainian schools and music schools, having no babysitting options to catch a breath after all the multitask challenges they face.

”Maybe Finland has been making Ukrainian women more independent and able to survive by themselves. They don’t have guys to help them in any situations. They have to do everything by themselves – because they must”, she says.

On Sunday, 26th of February there will be a number of memorial events by Ukrainian Association of North Ostrobothnia and its friends. The Orthodox Church will hold a prayer for Ukraine at 10:00, followed by a documentary ”The Nightingale Sings” about the struggles for Ukrainian language in Valve at 12. At 13.45 one can bring a candle and light it up near the stage on Rotuaari where at 14:00 Ukrainian songs will be performed and volunteers will say about the results of the year – the year of dignity and strength.